I wrote this essay a couple of years ago. It was included in Maternity Vacation, a book of Katarina’s work. I’ve revised the essay, my thoughts on the subject and my writing tightening with two additional years of being a person and a writer.

I discovered Katarina’s work on Instagram in 2020. Her posts offered a glimpse of her life in Corpus Christi, Texas and studio practice living far from any art metropolis. In her work I saw paint as a substance of merging: life with her husband and young child, the Texas landscape, fantasy and the act of painting.

Katarina Janečková Walshe’s paintings remind me of Charlotte Salomon’s Leben? oder Theater? (Life? or Theatre?) autobiographical pictures that represent a layered inner and outer reality. And I see comparisons to Louise Bourgeois who addressed motherhood in her work, but with a darker sense of humor and less tenderness.

I admire Katarina’s paintings. I equally admire the way she cultivates a full life on her own terms in partnership with courage and care. An artist’s power to resist dominant narratives and norms exists within and beyond their pictures.

ef

How to Be a Whole Person: The Paintings of Katarina Janečková Walshe

A Woman is split in half, bisected by what Freud called the Madonna-whore complex (also referred to as the Madonna-mistress complex). This tendency to position a woman within an either-or dichotomy–hypersexual lover or desexualized mother–is perpetuated in narratives and attitudes held by both men and women of various cultures, persisting over time.

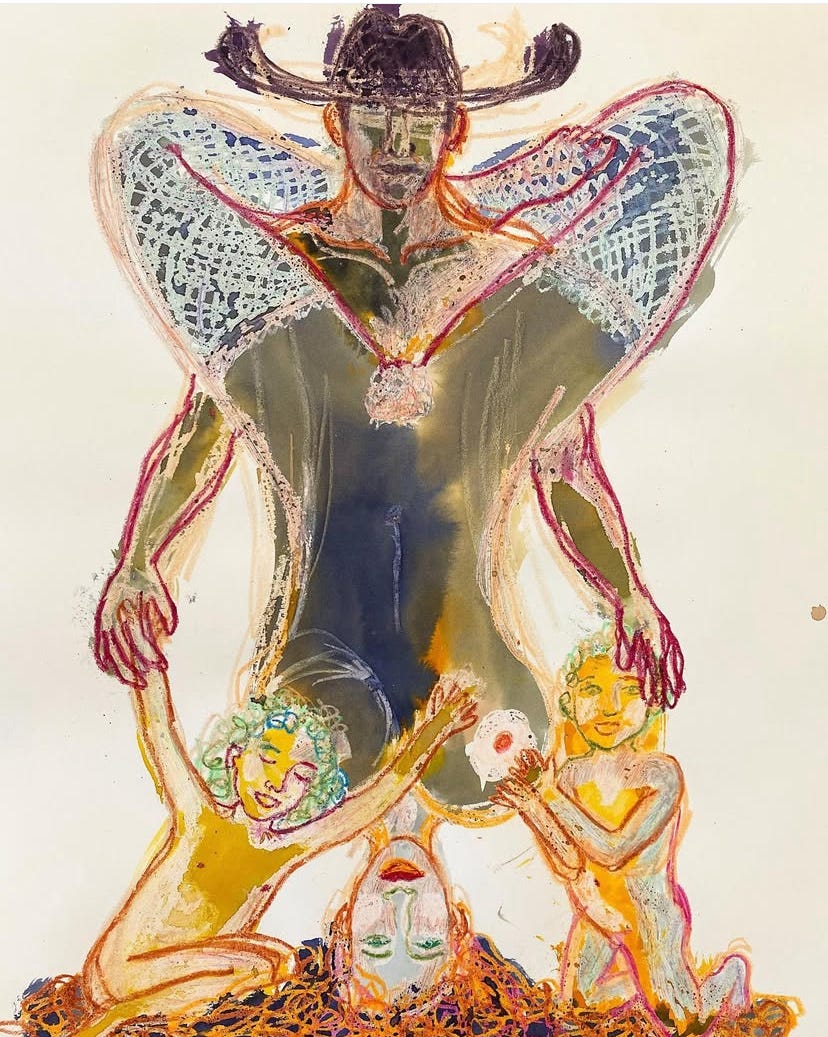

Katarina Janečková Walshe either ignores the Madonna-whore dichotomy, or deliberately upends it in her paintings. The artist proposes a sensual, fertile, and caring world in which a woman moves in her life and relationships able to remain a whole person in love, in partnering, in mothering, the multifaceted person she inherently is.

The woman in these paintings resembles the artist enough to conclude these pictures are based on the artist’s memories and fantasies. Painting is the unifying gesture that keeps the artist whole and pushes back on the idea that a woman must ever abandon part of herself to fulfill another part. But Janečková Walshe is not painting a manifesto; she is painting a diary, a searching, exploring record of her life and desires as a lover, a mother, and a painter and at the same time illustrating what it means to be whole.

The artist’s palette is warm, grounded in ochre, colors of her adoptive Texas while an occasional cool green landscape might recall her native Slovakia. The palette and brushwork sometimes feel calculated and sometimes improvised as if the nearest brush and color were taken up in a creative frenzy or moment of distraction. Some marks are made directly with her hand. The physicality of her work correlates with the physicality of what they depict, a tactile life.

The Lover

The role of the archetypal Woman-Lover is to please and be pleased by sexual attentions. The Lover is uninhibited and free of shame. A persistent societal bias renders the amorous man winning and virile, while the same enjoyment of and prowess in physical love in a woman invite judgement and degradation. The mistress-whore is without formal commitment, her position perceived as impermanent and insecure. The Madonna-whore model expects a lover to retire or play down her sexuality once she has children. The Lover in Janečková Walshe’s paintings remains intact in the context of domestic and family life.

The lusty, tender, awkward, sweet, and funny sexuality depicted In Janečková Walshe’s paintings is the indoor-outdoor love of Eden, pre-expulsion, before the fear of judgement. Her paintings of lovers are at times tender and at times vulgar like sex itself. The fact that her lover is often depicted as an animal, a bear, feels almost beside the point. A painting is always a fantasy.

A lover’s gestures are experimental, intuitive, and messy like a painter’s. Janečková Walshe depicts moments of humor, a butterfly touching down on the tip of a penis poised in front of the woman’s face, her eyes crossing slightly to observe it. Physical love is goofy, sloppy, and awkward.

The woman’s facial expression is calmly out of sync with the ecstasies or domestic labors that engage her. She smiles a wry smile, locks eyes with the viewer. The effect is layered time, reverie on top of memory, a daydream-in-progress, the return of a gaze. Like painting, physical love is not, at its most ecstatic, proper, prudish, or genteel. Paint is the perfect medium to address the messy, imprecise activities of love and sex, both requiring a balance of control and abandon to produce the most pleasurable results.

The Mother

The lovers’ gestures create new life. When a woman gives birth, the universe opens momentarily and a new being passes from elsewhere into this world. With whatever magical or scientific lens, you consider this event, its physics and metaphysics are impressive if not mind-blowing. On the other hand, the reality of childbearing and child rearing is utterly mundane. The flights of the Lover are brought to earth. In the Madonna-whore fallacy, the Mother is sexually set aside. She is respected, her reputation and position secure, but must forfeit the wild side of her nature and her identity as Lover.

The breasts that gave pleasure to the lovers, swell, produce milk, sustain life, and sag. The woman becomes a fountain of nourishment and she can be depleted. Her time and attention prioritize the child and, under the anxious influence of the Madonna-whore fallacy, this can upset the harmony between the lovers. The man turns away from physical love with the mother.

By contrast, the Mother in Janekowa Walshe’s paintings retains her role as Lover; she insists on it. She is the manifestation of abundance. The paintings propose (and document) a Mother-Lover integration with all its overwhelm and fatigue. In the face of the woman, we witness calm acceptance of the compounded tasks at hand: to remain connected to her lover while nourishing her child. In Janečková Walshe’s paintings, The Mother makes space for both Child and Lover.

The Child

The Child arrives, shifting the order of the world. The product of love, the Child is the unifier and the divider, infusing the life of the Lovers with new purpose while challenging the organization of all things. The Child is painted with lightness, simple lines and often less paint than the adults as they are new humans, still sketches, full of surprise and potential.

A child introduces new challenges to a mother who wishes to continue her creative practice. Nonetheless, Janečková Walshe’s paints, creating a constant bridge between the worlds outside and within the paintings. Janečková Walshe’s studio is not exactly a room of her own. She welcomes the child who paints, augments and disrupts the work her mother has made. The artist invites this collaboration in her studio with acceptance, humor, and curiosity.

The Man

It would be a mistake to believe that only the woman is debased by the Madonna-whore fallacy. In this scenario, the Father curbs rather than cultivates his desire for his partner, grounding their amorous fantasy and connection. He may then seek a new lover or he may be desexualized alongside the mother. Either way, the man trapped in the Madonna-whore narrative, experiences shame.

Janečková Walshe’s paintings reject shame and division; her subjects are free of its toxic burden. The Lover-turned-Father remains whole, both sexual and supportive. The Man is an animal, wild and tame, a bear in cowboy clothing. The Father learns to share the nourishing attention of his partner. He must, like the Woman-Lover-Mother, grow and evolve in their expanded universe that now includes the Child. The bear-Lover appears, disappears, and reappears in the paintings. He coexists with the Child, generously ( or possibly grudgingly) sharing the attentions of the mother, who nonetheless remains his Lover. The bear-Man, tame and wild, virile and tender, accepts his evolving role in the natural order that places the Woman in the center of their world.

The Painter

Like any act of creativity, the act of painting is a gesture toward being a whole person. Katarina Janečková Walshe paints like her existence depends on it and it does. She insists on a holistic life in which she can embody her inherent complexity. No individual can single-handedly undo the trouble the Madonna-whore dichotomy has caused, but a person can paint. She can paint the story of remaining whole. Katarina Janečková Walshe–the Lover, the Woman, the Mother, and Painter–shows us her world in warm Texas colors where there are dishes to wash, children to feed, love to give and accept–where everyone belongs, everyone is nourished, and everyone is whole.

Links

Katarina’s book - Maternity Vacation, her Instagram, her current show at Austin Contemporary, and Harkawik.

*I will update the captions soon. -e

A great description of her work!