Before I visited Rouffignac, in southwest France, I had imagined prehistoric cave drawings were found close to the mouth of a cave, ground-shift obscuring the entrance for thousands of years. The drawings in Rouffignac though, were not just inside the cave. To see them, I had to put aside some micro-terror about going underground.

The images in my Art History textbook diminished and flattened cave drawings, Lascaux probably, posing them in a timeline, which also flattened them temporally. I completed the unit, then literally and metaphorically turned the page. Years later, in France, I’d come to understand these drawings differently. All my senses were engaged; they moved me. The fact that prehistoric people made drawings never really surprised me; of course they did. What surprised me, the thing that moved “cave art” from an idea to something I felt in my body, was that these humans went a mile and a half underground to do it.

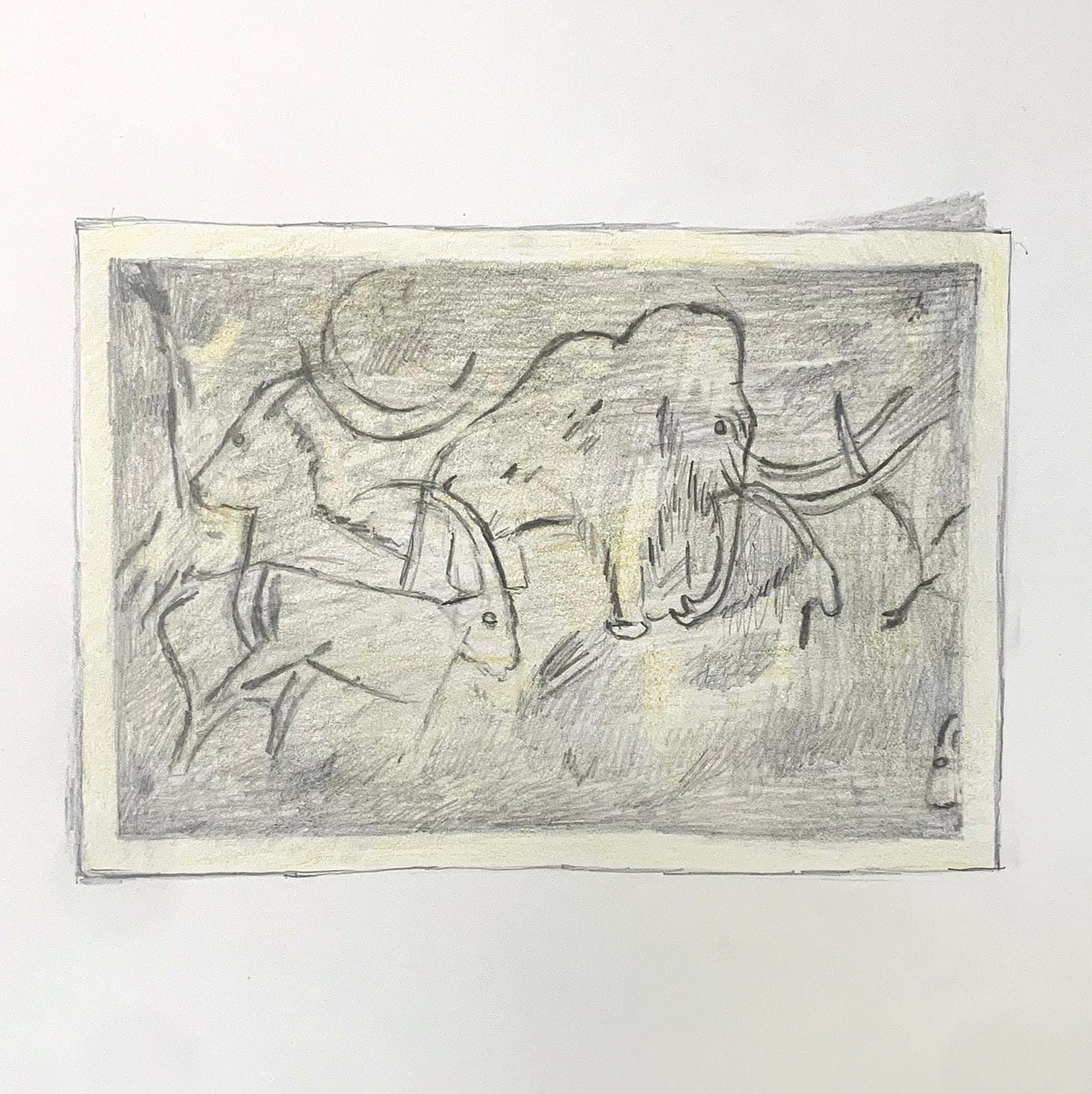

The Rouffignac cave is known as the Cave of a hundred mammoths because it contains sixty to seventy percent of all known Paleolithic depictions of mammoths. These massive animals once walked on the actual ground in Europe. Actual humans saw them in the wild (and it was all wild then). It’s possible to picture the mammoths in the verdant Dordogne, in a place we now call “France.” The mystery for me is the fact that earlier humans drew over one hundred of these animals (that they actually saw) on the walls of one certain cave.

In Rouffignac, we weren’t too far from the more famous Lascaux caves, which have been closed to the public since 1963 to preserve the site. I look at this fact sideways with a mix of relief and regret. I don’t like to think about the damage tourists cause, and I don’t like to think about art I’m not permitted to see. They’ve made a replica of Lascaux, and some reports are that it can’t be distinguished from the original. I’m skeptical. In Rouffignac, though, you can see the original drawings.

We bought tickets at the mouth of the cave, my two children, their father, and me. When it was time for the tour to begin, we sat two by two, on seats of an open electric train. The guide spoke in French, which was hard to hear at times over the English woman seated in front of us, reading to her family from the English language brochure. People, I thought, they make amazing things, and they ruin things.

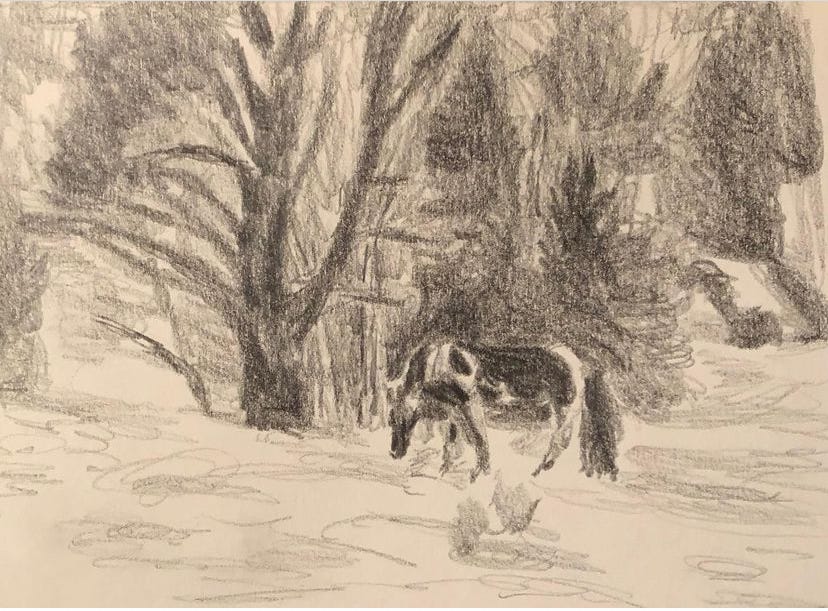

The train carried us slowly through the labyrinth, lit by dim electric lights. The guide pointed out scratches on the walls made by prehistoric cave bears sharpening their claws. Over a mile underground, the track ended in a small gallery with a low ceiling. The guide instructed us to get up and look around, en silence s’il vous plaît. I moved as far as possible from the English woman.

I’d never considered the quality of cave drawings, never responded to them as art exactly; I’d thought of them more as artifacts, and a prologue to the story that brought us to eventually Jeff Koons. But these drawings were beautiful, minimal, confident, and graceful. Still, the word “artist” seems strange here, as if this thing they did was integrated into their whole selves in a way that’s different now. I imagine the world before the notion of art careers, MFAs, exhibitions, priceless collections on oligarchs’ yachts, and the term “the art world.” Maybe all these people were artists. Maybe art was religion. Or maybe the people who drew the animals were shamans, the seers, the divergent thinkers.

In Rouffignac, there was a drawing of a baby mammoth so sweet it hurt to look at it. That was a few years ago, but I think about the caves at least once a week and maybe once a day. When I feel dispirited on my own path, I remember the Cave of a hundred mammoths, and those ancestors who made their way more than a mile underground in the dark to draw.

Here is an audio version of this post.

To draw is to make organized marks. The act leaves evidence of the mark maker: “I am here, now, in this very moment, marking my existence.” To make marks, to organize these marks, is utterly primal. Maybe this is why I cannot throw out my child’s drawings—even those with only 1 or 2 marks from when she was still astonished that her body could leave marks. Great essay, so thoughtful and thought inspiring. Thanks Emily!

Beautiful reading. Thank you Emily